Paper Review - Memory Barriers a Hardware View for Software Hackers

Overview

This article is a summary of the paper "Memory Barriers a Hardware View for Software Hackers" and discusses the underlying reasons why many synchronization issues occur and how to fix them.

Topics covered include

- the behavior of caches on CPUs with many cores

- specific methods for maintaining consistency

- what is a write barrier, read barrier

- different consistency management techniques for different architectures and how the OS handles architecture consistency regardless of CPU architecture.

Note:

- *May be easier to understand if you read the paper along with the article?

- the paper refers to the CPU as Core in the text

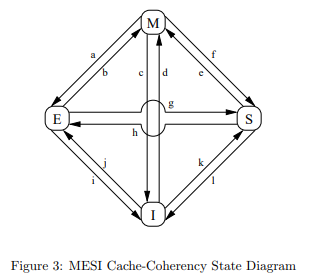

MESI

State

The cache of a CPU core has four distinct states

- Exclusive

- the value exists 'exclusively' in the core's cache

- Modified

- the same as Exclusive, the value exists only in the core cache.

- but if the value is changed and it has to discard its own value, it is obliged to reflect the value in memory

- Shared

- the value in the cache is shared with other cores

- Invalid

- the cache does not contain anything

State Diagram

State Transitions

The cache state of a core changes depending on the behavior of the core or the behavior between cores.

For example:

- Core1 has stored the exclusive value A in its cache.

- if Core2 sends a request to read that value

- Core1 tells Core2 what the value of A is

- the state transitions to Shared because A is no longer exclusively Core1's value

and so on.

Message

The aforementioned read request acts as the message that triggers the state transition.

The types of messages are

- Read: A read request to request cache information from another core.

- Read Response: an answer to the read request

- Invalidate: Invalidate the value in the other core's cache (delete the other core's value so that only you can have it)

- Invalidate Acknowledge: Acknowledge that you have invalidated

- Read + Invalidate: Request both Read and Invalidate at the same time (I give you a value and you invalidate it)

- naturally, both Read Response and Invalidate Acknowledge are required.

- Writeback: Write back the value from the cache to memory, which has the effect of freeing up space in the cache.

Problems and optimizations

MESI allows cores to be consistent about values that they do not share.

However, waiting for each other's request naturally incurs overhead whenever shared resources are used.

Prob 1: Invalidate + Acknowledgment

Sending a message is basically the same as sending data.

In other words, just as there is latency in data communication on the network, the CPU has to wait for an answer to the request, and that is the overhead.

In the above situation, in order to proceed with the write operation on Core0, I need to request Read + Invalidate from the other cores to check if my value is the latest value, and compare my value with the other cores' values.

In other words, there is an overhead of waiting for messages from the other side for comparison.

But *Does Core0 always have to wait for Core1 in the write operation?

In a write operation, my value will be written anyway, regardless of the latest value?

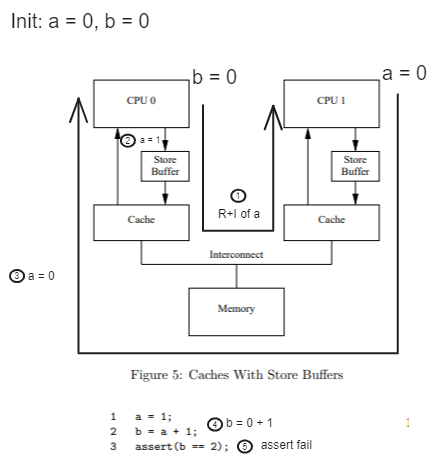

Store Buffer

This is where the Store Buffer comes in: a buffer to "mark" the value as written without having to wait.

With the introduction of the store buffer, commands that contain a store command can be executed immediately without waiting for a message from the other core.

However, the store buffer alone causes the following problem

[R + I = Read + Invalidate. The picture isn't neat enough;;]

Here's a quick summary of the flow

- through steps 1 - 2 - 3, Core0 executed a = 1 and stored the value 1 in a.

- but it was only written to the Store Buffer and not to the Cache.

- Core1 requests the value of a from Core0 in order to execute b = a + 1

- Core0 naturally hands over the value that exists in the cache (the value of a in the cache is 0)

- Core1 executes b = 0 + 1 and throws an error

The above problem is caused by a mismatch between the value in the Store Buffer and the value in the cache.

To solve this problem, we introduced a mechanism to check the values in the store buffer and cache.

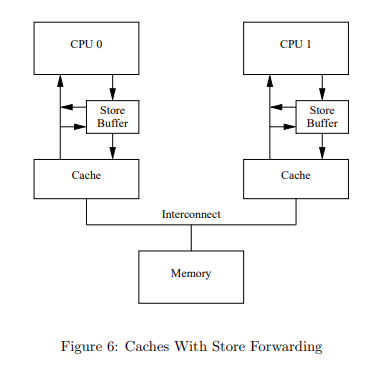

Peephole Cache (with Store Forwarding)

By creating the above structure, the problem is solved as follows.

Let's start again from 2. above

- core1 requests the value of a from core0 to execute b = a + 1

- Core0 naturally passes the value that exists in its cache (the value of a in the cache is 0), but checks the Store buffer before doing so

- checks the store buffer to see if it contains a

- passes the value in the store buffer, not the value in the cache

- Core1 executes

b = 0 + 1 and gets an errorexecutes b = 1 + 1 and everyone is happy

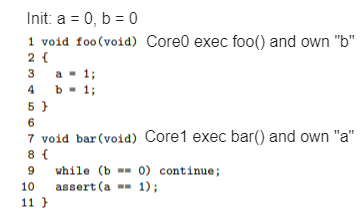

Store Buffer and the Write Problem

While it would be nice if everything went smoothly, there is still a problem that hasn't been solved.

The problem is that Core1 doesn't know the state of Core0's Store Buffer.

You might be thinking, What? Didn't you just say it could know?

Let's take one step back and check a unique case below.

If executed in this order

- a = 1 is stored in Core0's Store Buffer and it requests R + I from other CPUs

- b immediately updates its cache because it is the only one it has

- Core1 requests the value of b, which does not exist in its cache, via a "Read" message in order to execute b == 0.

- Core0 passes the requested value of b (b = 1) to Core1

- currently, Core0 has a in its store buffer and b in its cache.

- Core1 looks up the value of a to execute a == 1

- since a already exists in Core1's cache, the value is available immediately

- assert(a == 0) fails because Core1 has a value of 0.

- the R + I value requested by Core0 arrives late.

Exquisite cases like above can occur.

Naturally, Core0 will execute Read + Invalidate to get the value of a as its own, but Core1's code will be executed before it is invalidated, causing a problem.

The root cause of this problem is that by introducing Store Forwarding, we are guaranteed to get the latest value when we request a Read from someone else,

But, Core1 doesn't check the other core's store buffer when Core1 uses it's own value, which can cause inconsistencies in the data between each core.

Now you can see that there is a contradiction somewhere.

- You can't tackle Core1 is using it's own value

- Because, to solve this problem Core1 needs to check the value is exclusive, every time it use the value.

- If we do check every time, then why we use Store Buffer?

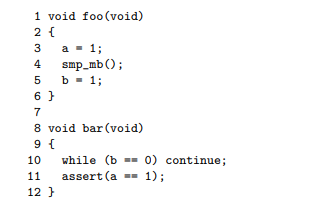

Memory Barrier

So how can we solve this problem?

The answer is simple.

We just need to actually operate the operations that we have only "marked" in the *Store Buffer.

Then the problem in the example above will not occur. Let's take a quick look

- Core0 requests R + I to execute a = 1

Store Buffer and it requests R + I from another Core- updates its cache immediately because b is exists in it, exclusively

- wait for R + I to reflect a = 1 in Core1's cache

- Core1 requests the value of b, which does not exist in its cache, via a "Read" message to execute b == 0.

- Core0 passes the requested value of b (b = 1) to Core1

- currently, Core0 a, b are in it's cache

a is in its store buffer.

- currently, Core0 a, b are in it's cache

- Core1 looks up the value of a to execute a == 1

- It requests the value from Core0 because it is in Invalid state

a already exists in Core1's cache, it can use the value immediately - the requested value arrives and Core1 can pass the assertion with a = 1

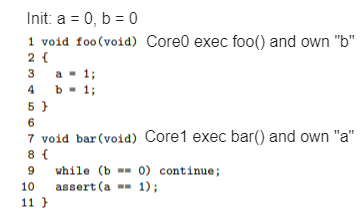

These operations cannot be handled automatically by the CPU and must be handed over to the programmer, because the CPU cannot know the dependencies between variables.

The Memory Barrier operation is provided to allow the programmer to control these data dependencies.

smp_mb() means to reflect all the values in the Store Buffer.

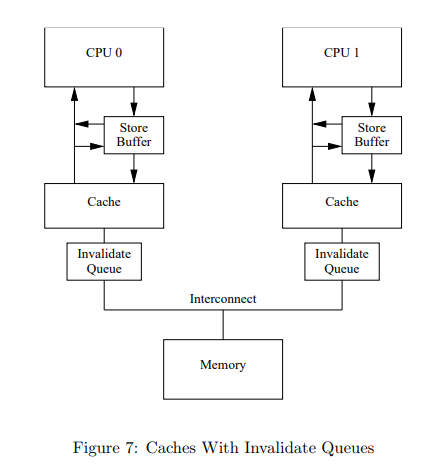

Invalidate Queue

While the previous problem solved the overhead for writes, let's look at the techniques introduced to solve the overhead for reads.

Another overhead that can be introduced by a multi-core configuration is the need to wait for Invalidate messages.

Every time we do a read, we have to send a Read + Invalidate message to make sure it's the most recent value, and then wait for the Invalidate message to arrive.

The overhead comes from this waiting. Consider a situation where Core1 is busy when Core0 sends a Read + Invalidate to Core1.

Core1 will Invalidate its cache to process this R + I message and send the Read value. It then has to process the Invalidate message while it is busy.

And if it needs to use the invalidated value again, it will have a cache miss (Double overhead!)

To solve this problem, we introduced the Invlidate Queue, which stores Invalidate messages as they are received.

Now, when the CPU receives an Invalidate message, it stores the Invalidate message in the Invalidate Queue and sends an Invalidate Acknowledgment instead of actually invalidating it.

The problem that the Invalidate Queue solves is that you don't have to invalidate every time an Invalidate message arrives.

The idea is to reduce overhead by just "marking" the cache line as invalidated and not actually invalidating it every time.

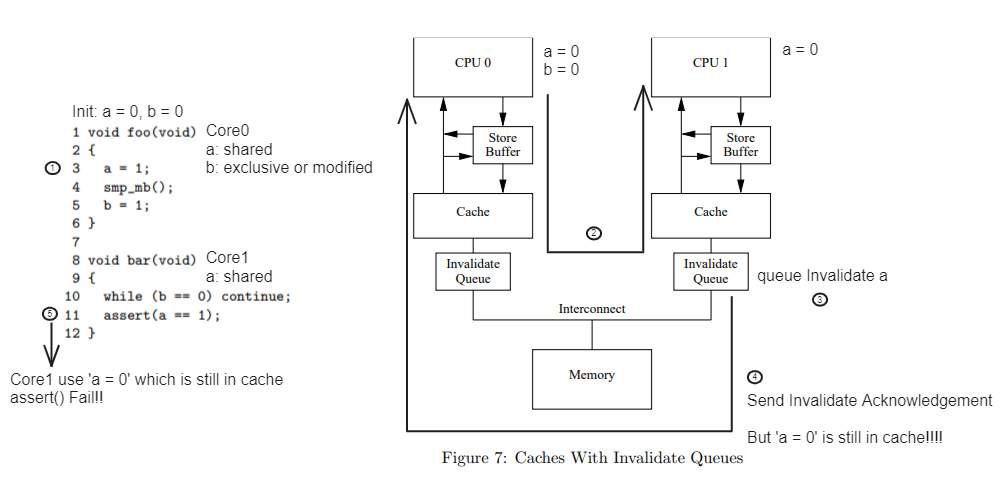

Invalidate Queue and Read Problem

The Invalidate Queue we've read about so far has many similarities to the Store Buffer mentioned earlier.

Before we move on, let's organize them a little bit based on their commonalities, because they can get confusing.

- Both mark a request when it comes in, instead of actually processing it

- Both reply to the request with a message that request is handled, regardless of whether the request is actually handled or not

- this results in

- Reduces overhead

- Creates value gap between core

So we can ask the same questions about Invlidate Queue as we did about Store Buffer.

Is it okay to send an Invalidate Acknowledgment without actually performing the invalidate.

The problem starts with this question.

The values in the Invalidate Queue are the values that should be invalidated in the future.

What happens if the CPU does not invalidate a value that should be invalidated?

The CPU cannot be sure that the values it uses in its cache are truly up-to-date.

What if the CPU thinks it is the most recent value and uses it?

- Core0 executes a = 1

- it sends R + I to Core1 because it is in shared state

- Core1 has no value for b, so it sends a Read request to Core0 to execute b == 0

- Core1 puts Core0's I + R request into the Invalidate Queue and immediately replies with an Invalidate Acknowledgment

- a = 0 is still in Core1's cache without actually invalidating it (Core1 is too busy to invalidate it right now)

- Core0 has b in its cache, so it immediately reflects the value b = 1 into its cache

- Core0 sends b = 1 in response to Core1's Read request

- Core1 can escape While(b == 0)

- Core1 executes assert(a == 1), which uses the value in its cache without any constraints since a == 1 only reads the value of a

- Core1 is too busy to check the Invalide Queue and the value of a is zero

- assert fails

(What a situation...)

Memory Barrier Again

So how can we solve the above problems?

The answer is exactly the same as the solution mentioned in Store buffer, the problem we just encountered would be solved if 'a' in the Invalidate Queue was actually invalidated.

If a had been invalidated, the assert() would not have failed because a would have been invalidated when we executed a == 1 in step 6, and we would have been able to make a Read request to Core0 to reflect the latest value.

Just like the Store buffer, we can actually invalidate the values that were only 'marked' as invalidated.

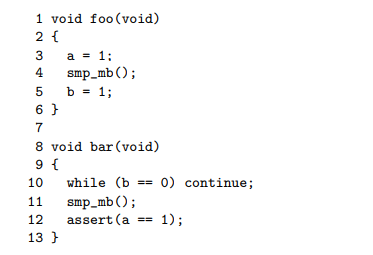

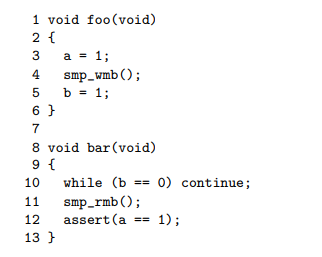

Read and Write Memory Barrier

The Memory Barriers described above are actually related to two operations, Read and Write.

We use the terms Read Memory Barrier and Write Memory Barrier for Read and Write respectively.

- Write Memory Barrier: Guarantee that writes are actually reflected

- Read Memory Barrier: Guarantee the most recent value for read

Using these words, we can replace the code in the image above with the following

If the code is written like this, the assert will not throw an error.

Let's think about the code, before step forward.

The condition assumes that foo and bar are being executed by their respective cores, just as in the previous case

The worst case is that an assert statement is thrown

So far, assertions have occurred in the following situations

- the value a = 1 is not actually written.

- the value read for a == 1 is not up to date

With the introduction of memory barriers, the above conditions are solved as follows

- the write barrier guarantees that a is 1(a = 1) at the time b = 1 is executed.

- This prevents the case where it hasn't actually been written.

- the Read barrier guarantees that the value of a read for a == 1 always reflects the most recent value of a

- i.e. if a = 1 was actually written, we can guarantee that the read value of a will always be 1.

- (conversely, if it was never actually written, it could be 0 or 1)

Appendix

We have seen how the MESI protocol can be used to ensure cache consistency on CPUs with many cores.

Next, we discussed the overhead of ensuring consistency and the various optimizations that have been introduced to address it.

Finally, we discussed the side effects of optimizations and what techniques exist and how they can be used to address them.

We've covered all but the last of the five goals we set out to accomplish in this article.

In the appendix, we'll cover the final topic, CPU implementation(=architecture), which is a bit of a mixed bag, and how memory barriers are handled in operating systems.

Memory Reordering and Execution Ordering

Although we didn't mention it in detail in the article, there is a strong correlation between memory barriers and the CPU's instruction execution order.

Note: Before reading this section, please note

- this is not the same as Out-of-Order Execution that you usually learn about when studying computer architecture

- out of order centers on processing variables that are not dependent on each other in a pipeline.

- this is about behavior when multiple cores interfere with a single variable in memory.

- although we didn't mention it before, we have already seen out of order execution when looking at Store Buffer and Invalidate Queue.

- before reading further, let's go back and think about it

- specifically, let's go back to Store Buffer and focus on what the actual order of behavior is

Below, we'll focus on an example from Store Buffer to see how the actual sequence of actions changes.

- a = 1 is stored in Core0's Store Buffer and requests R + I from Core1

- Core0 updates value of b immediately, because b is exclusive

- Core1 requests the value of b, which does not exist in its cache, via a "Read" message in order to execute b == 0.

- ...

The hidden answer to changing the execution order is the above two sentences.

That is, independent of the actual instructions executed by Core0, to an outside observer, a = 1 has not yet been reflected and only b = 1 has been executed.

This execution order is what we call a memory reorder.

Imagine that the above code is just a combination of Load and Store (or Read and Write).

Core0 would execute like

- store( or wrote) the number 1 into a variable called a, and

- store 1 in a variable named b

In the procedure above, programmer's intention was ignored and b = 1 was executed first.

Because Core0 was exchanging messages with Core1.

This situation is called Store Reordered After Store.

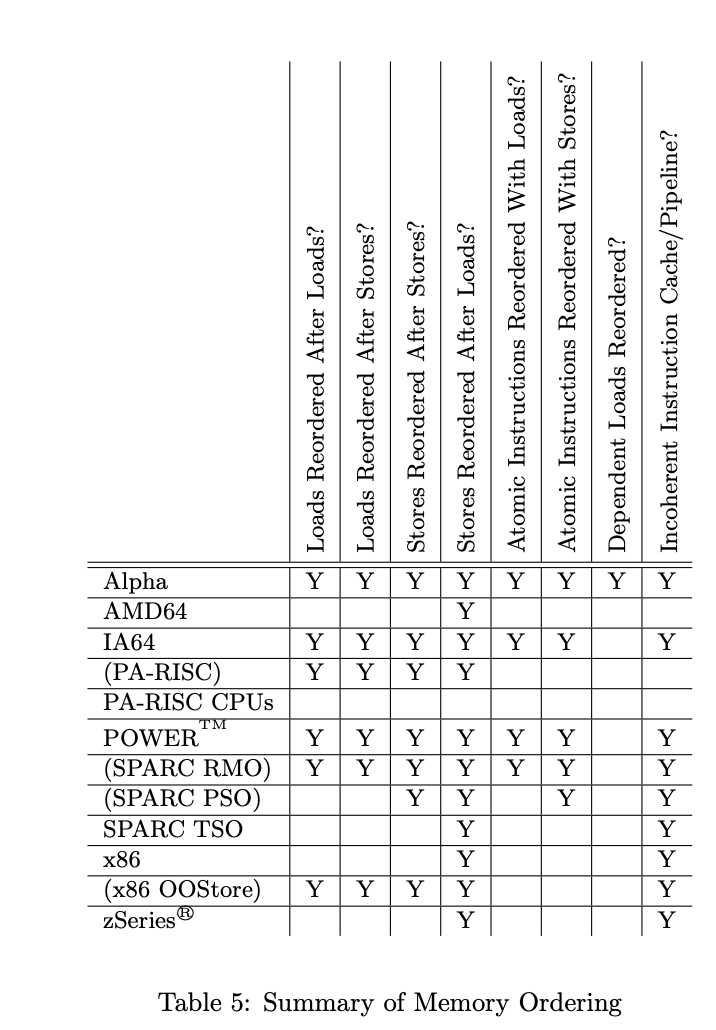

Architecture-specific features

The problem is that the memory reordering allowed by this CPU is architecture specific ;;;

[Holy - moly Guacamole!!]

The reason for this architecture-specific nature is optimization.

Different companies have different ways of handling instructions...

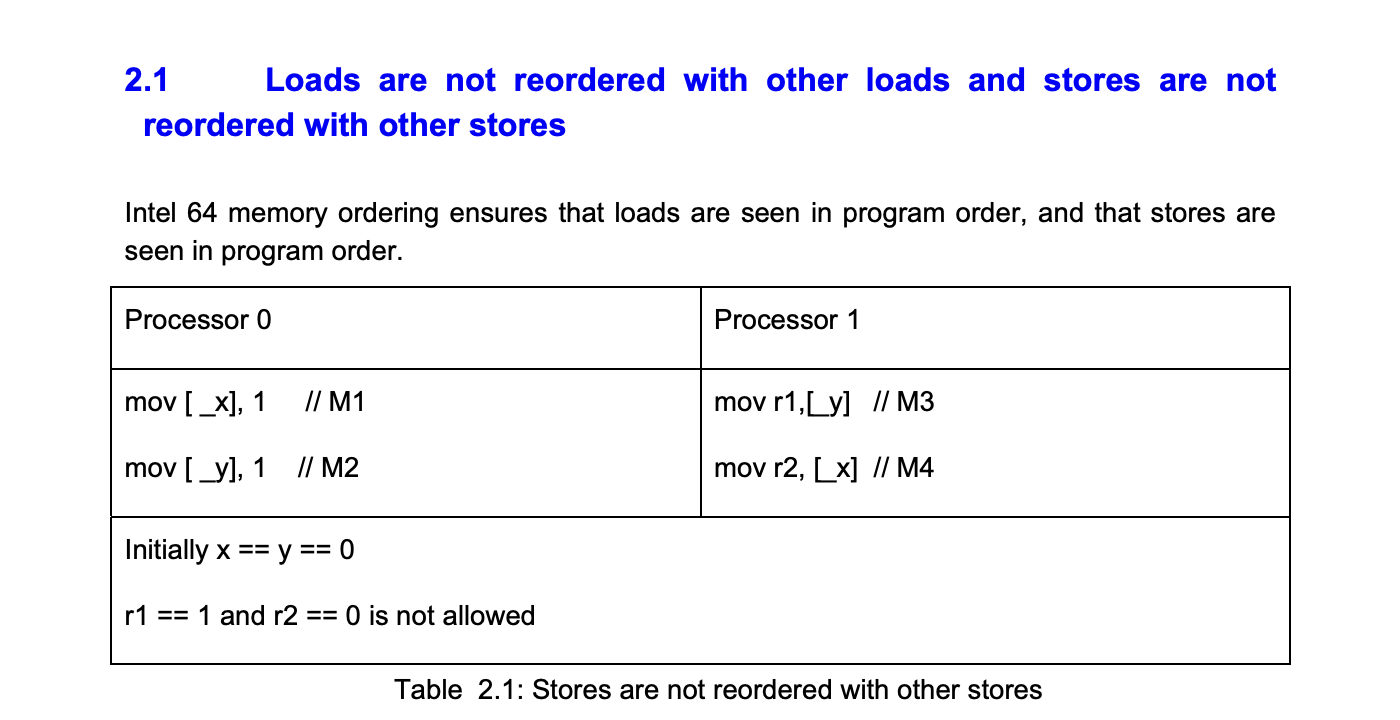

We'll look at the simplest x86 architecture as an example here

To keep it simple, we'll just look at load after load and store after store.

[Source - Intel® 64 Architecture Memory Ordering white paper]

The behavior that x86 does not allow is the following

First, if store after store(unauthorized behavior) is executed in

- mov [_y], 1 is executed first

- currently [_y] == 1, [_x] == 0 is stored

- processor 1 is executed

- r1 == 1 and r2 == 0

Next, we can think about the load after load

- mov r2, [_x] is executed first

- next, Processor0 is executed

- currently [_x] == 1 [_y] == 1

- next, mov r2, [_x] is executed

- r1 == 1, r2 == 0

This means that this behavior is not allowed on x86.

However, as briefly mentioned in the table above, there are CPUs with architectures that allow all of these behaviors!!!

But are we programming with these CPU architectures in mind, or are we not?

How is that possible?

How operating systems and languages deal with memory

The reason why we don't learn this stuff when we learn any language or study any operating system is simple.

It's because the interfaces provided by the operating system and the language are naturally abstracted enough.

Linux provides functions that give you direct control over these memory barriers.

However, in many synchronization-related functions we use, we don't usually think about this, because the functions are written so that we can write synchronization code for any number of cases, regardless of architecture!

In addition, more and more languages support multi-threading, which also takes into account the architecture of the CPU.

That's why programming languages also provide features that take into account the memory model.

Learn more

- What are the memory barrier instructions provided by Intel?

- Challenge yourself to read the paper!

- Read more about the SPARC architecture, especially the CPUs introduced in the paper.

- If you want to know more???..동기화의 본질 - SW와 HW 관점에서