Interrupt, Trap, Exception.. What's the difference - OS event(1)

Event

In this chapter, we'll learn about a really important concept in the operating system

It will also be a good refresher for those who have studied operating systems before.

After reading this article, you should have the following knowledge about

- have a basic understanding of what a process is.

- know how the keyboard and mouse work on a computer

- know what interrupts, traps, and exceptions are, which are important concepts to understand the operating system.

Interrupts? Traps? Exceptions?

As the title suggests, interrupts, traps, and exceptions can be defined as event.

So what are events for and why do we need them?

To understand that, let's go back to turing machine once again.

%20-%20BIOS%20%EB%B6%80%ED%8A%B8%20Boot%20Loader%EA%B9%8C%EC%A7%80/Pasted%20image%2020231213204547.png)

The picture above shows an early computer, the Eniac.

There are many differences between computers of the past and computers today, but the biggest difference we can see is the absence of a keyboard and mouse.

So how did people use computers in the past without keyboards and mouse?

Computers in the past were one thing

In fact, computers in the past were only responsible for one thing: calculating.

They were machines that people wrote code by hand, stitch by stitch, fed it in, and got the expected output.

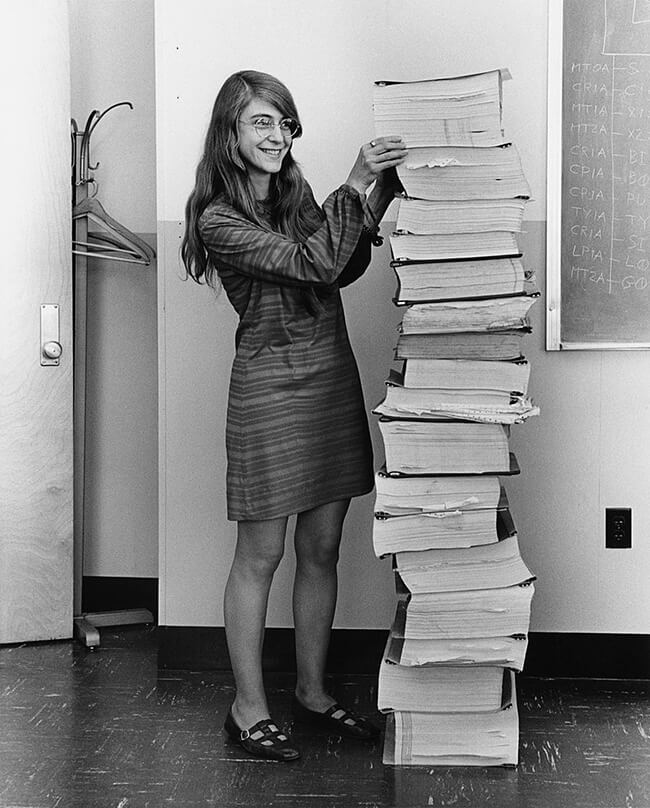

[Margaret Hamilton showing off her hand-written code]

If you put in code to calculate the trajectory of a rocket, or to land a rocket on the moon, you would get an output that would tell you how to adjust the attitude and correct the trajectory.

%20-%20%EC%9A%B4%EC%98%81%EC%B2%B4%EC%A0%9C%20%EC%9D%B4%EB%B2%A4%ED%8A%B8/Pasted%20image%2020231213211006.png)

In other words, you didn't need a keyboard and mouse because all you needed was code and input values to get the answer you wanted as output.

This would have been fine if the computer was just a machine for calculating orbits, but people wanted this great thing to be able to do more than just 'one thing'.

Modern computers

What is 'more than one thing'?

Importantly, the nature of computers' calculations does not change, but we use them to calculate Excel (statistics) or play games that are the result of another calculation.

The difference between now and then is that we are surfing the web while playing games, creating PowerPoints while doing Excel, and making calls on a discord while playing games.

These are what engineers of the past dreamed of.

The multitasking - playing games, talking on the discord, and doing schoolwork at the same time - and the result is the computer of today.

%20-%20%EC%9A%B4%EC%98%81%EC%B2%B4%EC%A0%9C%20%EC%9D%B4%EB%B2%A4%ED%8A%B8/Pasted%20image%2020231213212400.png)

How?

So how is this computer able to do multiple things?

How on earth can we play a game, listen to a lecture, and talk to a friend at the same time?

Before you scroll down, think about it based on the following hints: How did engineers solve this problem?

- even modern computers that are multitasking are actually doing a single computation (if they use a single core)

- the nature of computing hasn't changed

- CPUs are much, much faster than humans can experience.

The correct answer is

Computers take turns doing many tasks for a very short period of time.

%20-%20%EC%9A%B4%EC%98%81%EC%B2%B4%EC%A0%9C%20%EC%9D%B4%EB%B2%A4%ED%8A%B8/Pasted%20image%2020231214181452.png)

In other words, you are proceeding along the same lines as above.

This is pretty much what you'd expect, and some of you may have heard the phrase "computers pretend to do multiple things" before.

Now let's dive a little deeper.

To recap, we said that programs take turns running for short periods of time.

So

- How do these programs (powerpoint, discord, excel, game) switch?

- What is the switching based on?

Let's take a moment to clean up some terminology and OS theory here: the programs that are actually running are called process, and the process of switching between programs running on the CPU is called context switching.

So, let's get back to the topic: how does a program (process) switch between contexts (context switching) and what is it based on?

The essence of context switching will be covered later in process, but let's focus on how the transition (context switching) takes place.

The answer is surprisingly simple: issue a request to switch.

??? - but here's the bottom line.

- What is the conversion based on? --> Based on a request to replace

- How does the context switch take place? --> By acting (handling) on the request.

These requests are called events, and the behavior to resolve them is called handling the event.

Events and event handlers

So far, we've covered events and event handlers.

If you've been following along, you can expect that when you press or click the keyboard or mouse then events are occurred.

You can also expect the computer to call a routine (event handler) to handle the event when it occurs.

And as a result of the handler, we can expect the computer to receive our input.

In this way, we can see that switching processes (context switching) is also accomplished by an event occurring and calling a handler that handles that event.

Let's look at this in more detail using a 16-bit CPU as an example.

%20-%20%EC%9A%B4%EC%98%81%EC%B2%B4%EC%A0%9C%20%EC%9D%B4%EB%B2%A4%ED%8A%B8/Pasted%20image%2020231216134833.png)

[Source - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intel_8086 ]

The 8086, the classic 16-bit computer, has pins called INTR (Interrupt request) and NMI (Non-maskable Interrupt), which are used to check for events based on their signals.

Also, when an event occurs, an event handler is called to handle the event depending on the type of event, which is actually a function.

%20-%20%EC%9A%B4%EC%98%81%EC%B2%B4%EC%A0%9C%20%EC%9D%B4%EB%B2%A4%ED%8A%B8/Pasted%20image%2020231216141316.png)

[This picture contains a little bit of a lie-Note that IDTRs don't exist on the 8086]

This is the whole picture I just described.

Let's say IRQ 1 is an event for the keyboard.

The event handler goes through the following flow in the early stages of the OS (kernel).

- the CPU has the address of a table in the IDTR register that holds the addresses of handlers for the event, and the value of IDTR is set to the address of the IDT Table at OS startup.

- write a function in the OS (kernel) code that handles events for the keyboard (e.g. communicates with the keyboard as input is received).

- finally, register this function as a handler for IRQ 1.

The handler has the address of the function, so the IDT can be thought of as the equivalent of a function pointer list in C.

Now, when an event is generated by pressing the keyboard, the CPU stops what it is doing and calls the event handler corresponding to the keyboard input to resolve the generated event.

Calling the event handler is like calling a function, and the function proceeds to communicate with the keyboard before returning to what it was doing.

Appendix

See also - Switching Processes

In order to cover the scheduling of processes in the following chapters, it is worth mentioning the above-mentioned transition of processes.

Process switching is usually executed based on a timer.

Modern CPUs have an internal alarm and it is possible to set it to notify periodically.

For example, let's say we have an alarm set to go off every 1s second. If we can keep track of how long a process has been running, we can think of the following logic.

Register a function to check the execution time of the processes as an event handler of alarm

If the processor's execution time is too long when the alarm goes off, we can run another process!

This is very abstract, but this is how schedulers usually work.

Interrupts, Traps, and Exceptions - Types of Events

So far, we've covered what events are and detailed examples of them.

So why we don't simply use 'event' instead of all those terms like 'interrupt,' 'trap,' and 'exception.'

We used the keyboard as an example above, but there are many other events that can occur.

As we've said all along, OS is all about resource management, and process management is one of them.

Let's say a process throws an error, or the process itself terminates.

A process can artificially raise an event to signal its error or termination.

There may also be cases where a process wants to ask the OS to do something (a prime example is system call, which you will learn about later).

To accomplish these goals, the CPU has an instruction that artificially generates an interrupt called INT n.

Here, events generated by the keyboard and processes are called hardware interrupts and software interrupts, respectively.

Other terms, such as trap and exception, do not have a precise distinction (in fact, they are more like terms used in the developer's manuals of various CPU companies (Intel, ARM, AMD, etc...)).

In general, however, a trap is equivalent to 'software interrupt' and an exception is an event that occurs when a number is divided by zero or a non-existent instruction is received.

Glossary

In addition to the terminology for events described above, many of the same concepts discussed in this chapter are referred to using other terms.

You may hear them again in the future, so let's keep them straight.

Interrupt Vector Table (IVT)

The table that usually registers handlers for interrupts is called the Interrupt Vector Table (IVT).

We saw above that these tables are actually lists of function pointers.

This function pointer is usually defined in operating system theory as an Interrupt Vector.

And the table is called the Interrupt Vector Table.

Interrupt Service Routine (ISR)

Another term for this is the Interrupt Service Routine (ISR).

In this case, it is similar to the handler that handles events for the keyboard described above.

The process of calling the handler when an event occurs and returning the result is called 'servicing an interrupt', and the entire flow (routine) is called an 'Interrupt Service Routine'.

IRQ (Interrupt Request)

The last term is IRQ, which we used above.

IRQ literally means Interrupt Request.

As we saw above, an IRQ has a number and calls the handler registered with each number, and when we generate an IRQ, we say 'we have requested an Interrupt or generated the nth IRQ'.

8086 A little more detail

When we looked at the 8086, we saw that there are two pins, INTR (Interrupt request) and NMI (Non-maskable Interrupt), for generating interrupts, but we only looked at INTR.

Of course, both INTR and NMI are related to the same interrupt.

Let's take a closer look at the different types of events and their management.

For more information, see [[iAPX_286_Programmers_Reference.pdf]].

In practice, interrupts are subdivided into a number of different categories, usually based on the following criteria

- the source of the interrupt (software, hardware)

- Maskability (INTR, NMI)

- priority (Priority)

We have already explained the first one, so let's start with the second one.

Mask is to determine whether or not an interrupt should occur.

Imagine if you were processing an event on the keyboard, but a different event occurred each time, causing the keyboard input to be ignored (annoying!!).

The CPU can be configured to ignore the occurrence of interrupts, either by a command (the Clear Interrupt Flag (CLI)) or by making the handler for a particular interrupt ignore calls to it.

Controlling the occurrence of these interrupts is called masking, and masked interrupts are ignored.

However, certain interrupts are impossible to mask (i.e., impossible to ignore) and are called non-maskble interrupts.

For example, if we consider an OS in a car, and the car's steering wheel is an Input, we can see that ignoring the input to the steering wheel is more dangerous than simply ignoring the input to the keyboard.

Finally, interrupts can be categorized by priority.

Prioritization exists to allow for features such as having a higher priority interrupt fire if multiple events occur at the same time.

In our car example, we can think of the input to the steering wheel as a high priority event.

What if interrupts occur at the same time?

How does the CPU handle multiple interrupts at the same time?

The answer to this question is actually "It' depends on implementation".

For example, we can think of some implementations: storing simultaneous events and processing them sequentially, prioritizing the more critical ones, and discarding less relevant ones. (Understanding the operating system requires familiarity with the hardware, after all.)

In case of 8086, it uses an additional chip, the Intel 8259, to handle interrupts from various devices.

So what is the Intel 8259? and how it deals with multiple interrupts?

The Intel 8259 uses two registers to indicate the progress of a service

The IRR is used to store all the interrupt levels which are requesting service; and the ISR is used to store all the interrupt levels which are being serviced.

Intel - 8259A PROGRAMMABLE INTERRUPT CONTROLLER

In other words, each register marks the device's interrupt request and service completion, and if there are multiple requests, the interrupt is processed first based on priority, etc.

For more details, please refer to

Usage

Interrupts are used in a bit more varied cases.

By examining each of these uses, you can learn more about the operating system.

- DMA: Direct Memory Access

- Debugger: Single-step Execution

- IPC: Inter Process Communication Interprocess communication

It's especially interesting to look up Single-step Execution, which is used for debugging.